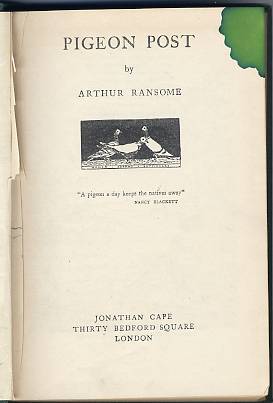

I have been buying and collecting books since I was very small. The book in this review – Pigeon Post by Arthur Ransome – is one of the earliest acquisitions that I still own. At the age of eight, in 1949, I was given it as a Christmas present. I adored the book, and read all the rest of Ransome’s children’s books by the time I was ten. I am not the only boy or girl to be captivated and inspired by Arthur Ransome’s books. The sailing world is packed with people who were given their first tastes of maritime matters by the Swallows and Amazons series.

I subsequently lent Pigeon Post to a boy I thought was a friend, and he vandalised it, destroying the dust cover and writing his name – HIS name – and much else of a trivial and dishonourable nature, together with childish doodles, on the blank sheets at the beginning and… go figure… spilled GREEN ink on it! I asked him to replace it, but all he did was to hack out the pages he had written on, and return the book. I did not learn from this experience. I have suffered many similar blows, notably the loss of my first set of Lord of the Rings hardbacks to a larcenous lendee in 1965, and my Catcher in the Rye early edition to someone who has always denied having it. But I cannot help, it seems, trying to spread the word of books I enjoy.

Still, back to Pigeon Post. I am not going to say anything about Ransome himself. His own life was remarkable indeed, but I am confining myself to the Lakeland children’s books.

My first impression of Pigeon Post, at the age of eight, was one of slight confusion. I had read quite a few books by that age, some of them quite complex for a young reader, like Treasure Island, Oliver Twist and The Children’s Bible. I was also familiar with fantasy by that age. One of my favourites then was A. Turnbull’s Mr Never-Lost – witches and such, and I had read much of Hans Christian Anderson and the Grimms.

Pigeon Post confused me partly because I had landed in the middle of the series. However, I was also bewildered because the book appeared to be set in a recognisable England, yet the children involved acted as though they were in a foreign country, and had their own placenames and private preoccupations that did not seem to match up with real life.

Most of Ransome’s “Swallows and Amazons” books have a degree of what would now probably be regarded as “Magic Realism”. Peter Duck and Missee Lee, in particular, are unsettlingly unlikely. The secret, new to me at the time, was that the children were adept at living an imaginary life within a real one. Throughout the book, adults are referred to as “natives”, the Blacketts’ uncle is referred to as Captain Flint, the Blacketts live on the banks of the Amazon River in the Lake District, across the lake from a village called Rio, near a hill called Kanchenjunga, their bicycles are dromedaries. This partial disjunction from reality is now what appeals to me in these books. And I mean “partial”. There isn’t a great deal of real fantasy here – just enough to render what they do from day to day a little more thrilling.

Most of Ransome’s “Swallows and Amazons” books have a degree of what would now probably be regarded as “Magic Realism”. Peter Duck and Missee Lee, in particular, are unsettlingly unlikely. The secret, new to me at the time, was that the children were adept at living an imaginary life within a real one. Throughout the book, adults are referred to as “natives”, the Blacketts’ uncle is referred to as Captain Flint, the Blacketts live on the banks of the Amazon River in the Lake District, across the lake from a village called Rio, near a hill called Kanchenjunga, their bicycles are dromedaries. This partial disjunction from reality is now what appeals to me in these books. And I mean “partial”. There isn’t a great deal of real fantasy here – just enough to render what they do from day to day a little more thrilling.

Despite their imaginations, the children are intensely practical. In Pigeon Post, they methodically set out to find gold in the nearby hills. They research, find what they are looking for, extract it and attempt to make an ingot for Captain Flint. All the science in the book is perfectly sound. They use pigeons as long distance messengers, they communicate with each other in semaphore and morse code, they can look after themselves in the countryside, far from adults. They are, to a large extent, sensible, responsible, polite and trustworthy. Though adults are a foreign race, they are prepared to deal with them maturely.

Of course, they make mistakes, which is where the thrill comes in. Pigeon Post has several incidents that are tense, but they are neither unlikely nor particularly life-threatening. They are given a degree of freedom that no English child would be given today, on the basis that they will act responsibly, which they do, for the most part. Pigeon Post, like all the Lake District books, I think, is set in the school holidays, and the children seem to attend boarding schools, though little is made of their lives in term-time. They come from respectable middle-class families. The Walkers (Swallows) are a naval family, the Callums (D’s) are academics. Some consider Pigeon Post to be the most mature of the children’s books, as it deals with work rather than play.

Arthur Ransome’s children’s books are no longer à la mode, I know. Apart from their 1930s setting, though charming in itself, they seem a little élitist, or at least bourgeois, in these egalitarian days. They are also filled with sailing terms and with Nancy’s strange exclamations such as ‘Shiver my timbers’ and ‘Jibooms and bobstays’. There is also the rather unfashionable contraction of Letitia’s name to Titty – childish humour, say no more. They speak of Victorian standards of discipline, trust, respect; but they also advocate self-reliance, enterprise and imagination. Amidst the stark world of modern child literature – disfunctional families, drug and alcohol addiction, parental divorce, bloodthirsty fantasies, I really hope there’s still room for the cosy, respectable world of Arthur Ransome.